|

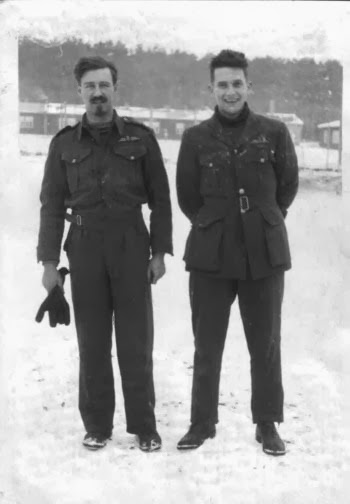

| Oflag XX1-B photographed in 1945 after it had been reopened as Oflag 64 and prisoners had left - Robert Keith |

Tunnel Asselin

In the final post around Long Tunnel Schemes, the Asselin

tunnel (sometimes named after POW French Canadian Eddy Asselin who was in

charge of the operation) could easily be described as ‘the pits.’ It is not a

good mealtime read, but illustrates just what lengths POWs were prepared to go

in order to try and break out of captivity.

|

| As per photo 1 - Robert Keith |

Oflag XX1-B in Szubin Poland was a POW camp for officers and

had been built in the grounds around a former school. Six brick barrack huts were

positioned on either side of what used to be the playing fields. In September

1942, British and Commonwealth Officers of the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air

Arm were transferred in from Oflag VI-B at Warburg following its temporary

closure (see post ‘X and the Wire Schemes’). The POWs also included airmen from

Poland, Czechoslovakia and other occupied countries serving in the RAF, as well

as flyers from the Allied Air Forces - RAAF, RNZAF, RCAF, SAAF, USAAF. In

October and November 1942 more British RAF Officers and NCOs arrived from

Stalag Luft III to help relieve overcrowding there. As the war in the skies

intensified, the inevitable steady stream of newly captured British, American

and Allied Air Force Officers also arrived from Dulag Luft.

A hard core of regular escapers were soon in situ and began

absorbing the geography and structure of the camp. They had no intention of

staying. Just a few of them have been listed below. The names are formidable:

Lt Commander Jimmy Buckley - Had been Big-X

‘Wings’ Day, B A 'Jimmy' James and John ‘Johnnie’ Dodge - See

previous posts

|

| Flt Lieutenant B A 'Jimmy' James |

|

| RAF Sgt Per Bergsland - One of the three Great Escapers to later make a successful home run (see previous posts) - (Jonathan Vance, University of Western Ontario) |

Flt Lts Oliver Philpott and Eric Williams - Later escaped from

Stalag Luft 111 via ‘The Wooden Horse’ and made it to Sweden

|

William Ash RAF 411 Squadron - American born pilot who relinquished his citizenship to join the RCAF and fly Spitfires. An iron willed and repeated escaper with unshakeable resilience and determination. Had endured numerous beatings and interrogation by the Gestapo. Later became a journalist and writer.

|

|

| Flt Lt Peter Stevens RAFVR 144 Squadron - Habitual escaper and nuisance to the enemy - Claire A Stevens |

PO Jorgen Thalbitzer RAF 234 Squadron - A Dane who had joined the RAF and changed his name to John Thompson to protect his family still living in Denmark.

|

| RAF Pilot Robert Kee - In the thick of escape work. Historian and future author. |

|

RAF Pilot Anthony Barber - Future politician and Lord Chancellor.

|

|

| RAF Officer Aidan Crawley - In charge of security at Oflag X11-B. Author, County Cricketer and future MP - www.in.com |

|

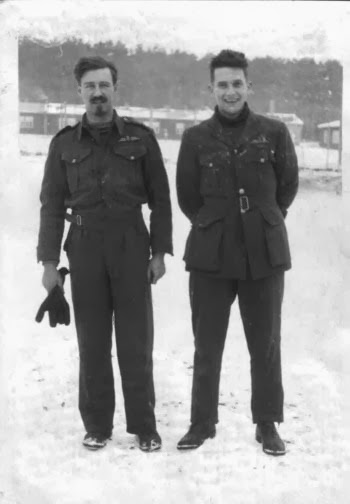

RAF Squadron Leader Dudley Craig (left) - A number of breakouts resulting in recapture. Involved in ‘The Wooden Horse’ and Great Escape. One of the regular POWs using the vaulting horse whilst the digging went on below. Unable to get out of the tunnel in the Great Escape before it was discovered.

|

Conditions in the camp were grim, with poor rations apart

from the lifeline of Red Cross parcels. There was jaundice, lice and the prisoners

had minus 15 degrees of Polish winter to look forward to. Tunnelling during

the main winter months was often restricted because of the weather, frozen

ground near the surface and the chances of survival in the cold once out of the

camp.

On the approach towards Christmas 1942 the POWs decided that

possibilities existed for a tunnel to begin from the latrines, which were in a terrible

state. The thinking focused around the guard’s likely reluctance to search and

poke around to any degree in an open sewer that served the whole camp. The

latrine building was around 150 feet from the wire, which meant a long tunnel.

The practicalities and effects of working in the latrine area were less than palatable,

but a decision was made to start the digging.

German microphones positioned in the ground to detect underground

workings were not seen as a huge obstacle. The POW’s camp intelligence system

had ascertained that any sounds of excavation during the daytime merged into

the sound of POWs walking around above, because the microphones were too

sensitive. It was decided to have regular groups of POW’s pacing about above

and stamping their feet to try and get warm.

Tunnel Method

1) Sunk to a depth of seventeen feet below ground.

2) Entrance made under the end toilet hole of the communal

latrine. The last seat was beside a wall that divided the latrine building in

two. This wall continued down under the concrete floor and separated an

underground sump on one side from a huge sewage pit on the other.

3) The diggers chipped away around the toilet base until the

whole unit could be removed and put back quickly. It concealed the initial entrance

which led to the main tunnel workings. The entrance hole was fashioned out to

be just large enough for a man to crawl through.

4) A false section was created to the hole and disturbance

in the dividing wall. This was removable and could be put in to conceal any

activity if the Germans came in to the latrines.

5) In the underground sump, a large working chamber was

excavated and the dirt pushed through into the latrine pit on the other side of

the wall. This avoided the usual methods of disposing of tunnel dirt. Once the

chamber was big enough for a man to work in, the tunnel proper was

started.

6) To enter the workings it was first necessary to squeeze

through the hole where the toilet seat was, come within a few inches of the

lake of sewage, wriggle through the hole in the wall and reach the chamber and

tunnel entrance.

Working in virtual or complete darkness and barely being

able to move in the stink and cling of clay or the filth which sometimes washed

in from the latrines was hideous in itself, but William Ash described how the

taste of the tunnel also filled the mouth when earth fell from an unshored part

of the roof and the digger’s mouth was already open gasping for air.

Tunnel Size

Two feet square

Stooges (Lookouts)

1) General lookout system outside the latrines and tapered

away to a suitable distance.

2) Stooge sitting authentically on the toilet seat guarding

the tunnel entrance and ensuring no one used it whilst workers were below.

Digging Tools

1) Scoops made out of old tins

2) Home-made knives

Shifting the Dirt down the Tunnel

Large bag tied to a long piece of string. This was hauled

back to the disposal team who scooped out the dirt with cans, throwing the soil

into the main latrine, then prodding the contents around to mix them in. As the

tunnel distance increased, men were positioned mid-way to take the bag and

reposition it before being hauled back by a man at the entrance.

Shoring

Bed boards from around the camp. Cave ins were frequent and

POWs were approached to give up a bed board or more.

Manpower

Thirty men on the project working in three shifts of eight.

First shift would dig, second shift dispersed earth, (mostly in the latrine pit)

and the third shored up and secured tunnel after the digging session. Progress

was hindered by additional Appels from

the usual two a day, which meant diggers often had to come to the surface and

get cleaned up as best as they could to be ready for the ‘parade’ and checking

off of names. Despite this, the team managed to hack out a few feet on some

days. Diggers worked naked whilst in the tunnel.

Air for the Tunnel

1) An old army kit bag converted to bellows.

2) The air pipeline was made of dried Klim milk tins from

Red Cross Parcels joined together (method later used in the Great Escape.)

Light

Lighting long tunnels was always a problem as the length

increased. Lamps fuelled by margarine were used with the wick from a boot lace.

Geography outside the Camp

1) Constructed and mapped as per standard systems covered in

previous posts. E.g. views from inside the wire, camp intelligence information,

specifics given by anyone who had escaped and been recaptured (after release

from solitary confinement) and also details from new POWs coming into the camp.

2) Additional information was obtained following the death

of one of the officer POWs. Wings Day as Camp Senior Officer was allowed to attend

his funeral held with military honours in the nearby village. He memorised the

surrounding area, passing the intelligence on to the escape committee and rest

of the team.

By the beginning of March 1943 the tunnel was almost ready,

but reliable intelligence had been received that there were plans to move the

prisoners to Stalag Luft 111. (some had been there before they were sent to Szubin).

It made immediate completion of the work essential. The tunnel was completed by 3 March and a decision was made to

move on the 5th as there was not much moon that night.

Numbers to Escape

As many men as possible to fit in the tunnel ‘head to toe’ for a

few hours after evening Appel without

suffocating. Given the physical numbers, proximity to the main

sewage pit, cess pool, latrines and size of the tunnel, there was no margin for

error. Thirty three men would have to lie there in terrible conditions (half in

the tunnel and half jammed into the cavern area near to the entrance), the only

light being from margarine lamps if they managed to burn in the foul

atmosphere.

Any cave ins would almost certainly result in fatalities.

Personnel

Those involved on the team would go plus John ‘Johnnie’ Dodge,

'Wings' Day and security chief Aidan Crawley. The men had all been

equipped with various ‘civilian’ clothes and forged papers.

|

| 'Wings' Day- IWM |

|

| Major John ‘Johnnie’ Dodge - IWM |

Exit

On 5 March after the last Appell at around five pm, the escapers

gradually wandered towards the latrines either singly or in a gradual straggle.

A rugby match was taking place as cover on the exercise ground nearby and none

of the guards seemed to notice that fewer men were coming out of the latrine

than went in. The men crawled into the two foot square tunnel wedged one after

another in the darkness. The air being pulled in by the bellows came from the

stinking latrine pit nearby and must have been indescribable. As the escapers

lay waiting in the tunnel, the camp cesspool began leaking over them.

The final opening of the tunnel and fresh air must have been

indescribable to the first few POWs waiting at the far end.

Escape

The tunnel opening came up clear of the wire, exactly where

they had calculated. All thirty three prisoners got out and clear. An

additional escaper followed in broad daylight the following morning before Appel when Squadron Leader Don Gericke a

South African, noticed there were no signs that the tunnel had been discovered.

He quickly located some escape rations, crawled down the tunnel and walked

casually away trying to look like a local. He was soon recaptured. Thirty one

of the thirty three were also captured, but some of the good German speakers

covered significant miles before being apprehended. Two escapers were never taken.

Former Big- X Jimmy Buckley and the Danish pilot Jorgen Thalbitzer were the two

escapers not recaptured. The two men travelled together and managed to reach

Denmark. Having been unable to board a ship, they were lost trying to paddle

across to Sweden in a canoe on 29 March 1943. Thalbitzer’s body was later

washed ashore, Buckley was never found. It is possible that they were struck in

the dark by another vessel.

|

| Lt Commander Jimmy Buckley |

|

PO Jorgen Thalbitzer

|

An estimated 300,000 personnel were out searching for the

escapers; soldiers, militia, police, Hitler Youth and civilians. In terms of

disruption to the enemy, that tells its own story.

Sources:

National Archives

Under the Wire – William Ash with Brendan Foley (highly

recommended read)

Author’s notes

©Keith Morley

THIS BLOG claims no credit for any images posted on this

site unless otherwise noted. Images on this blog are copyright to its

respectful owners. If there is an image appearing on this blog that belongs to

you and you do not wish for it appear on this site, please message me with a

link to said image and it will be promptly removed.